Yesterday I found myself trying to recall how to pronounce the Lakota saying: Mitakuye Oyasin, which I have admired for the longest time now. I learned its meaning when I first heard it, but how to say it properly … well, you know … advanced years … I forgot.

The phrase translates in English as “all my relatives,” “we are all related,” or “all my relations.” It is a prayer of oneness and harmony with all forms of life: other people, animals, birds, insects, trees and plants, and even rocks, rivers, mountains and valleys.

Wikipedia: Mitakuye oyasin

There is a Native American musical group called Brulé, and it was from them that I learned the meaning. The leader of the band, Paul LaRoche, had grown up in Minnesota and while he knew that he was adopted, his adoptive parents had told him that he was “French Canadian.” After their death, while going through the parents’ papers, he discovered that he was not Canadian at all, but Native American. A search for his origins brought him to the Lower Brule Reservation in South Dakota, where he met blood relatives for the first time.

With his daughter and son he formed the groups Brulé and AIRO, which have earned many honors and have one of the longest running concert videos on PBS.

***

******

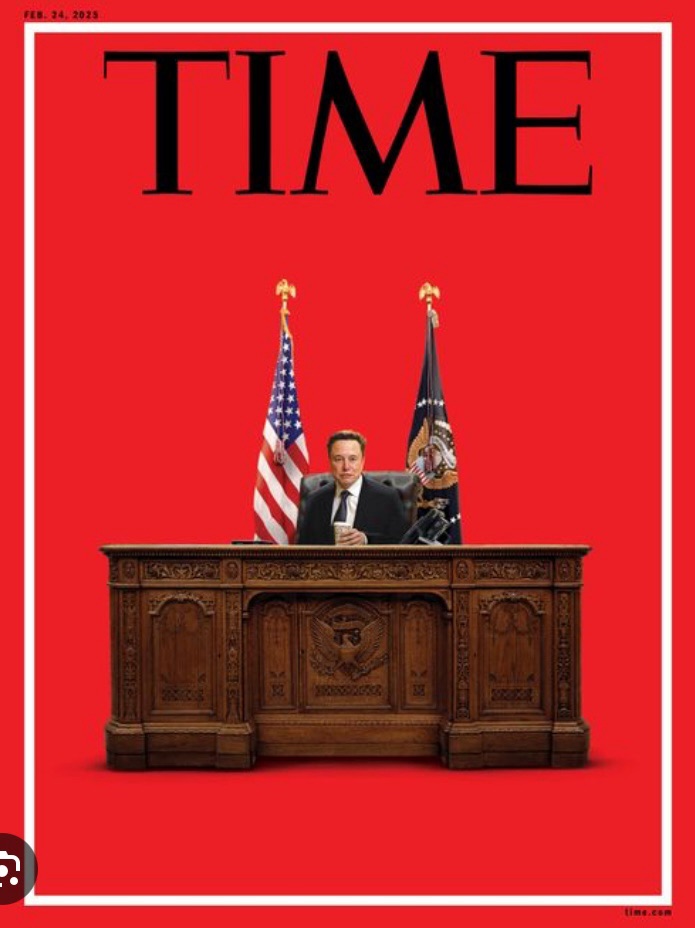

From The New Yorker

******

I grew up being immersed in the stories of the European pioneers, especially in the Midwest. Of their courage, steadfastness, and their hard work in establishing themselves in a new world surrounded by hostile Indians. Movies continued my miseducation, and were mostly on the theme of John Wayne beating down one tribe after another when they wouldn’t “listen to reason.”

But at the age of sixteen I read an old book entitled A Century of Dishonor, which chronicled the chicanery, lies, deceptions, and murders that eventually robbed the Native American of most of their lands.

The book consists primarily of the tribal histories of seven different tribes. Among the incidents it depicts is the eradication of Praying Town Indians in the colonial period, despite their recent conversion to Christianity, because it was assumed that all Indians were the same. The book brought to light the injustices enacted upon the Native Americans as it chronicled the ruthlessness of white settlers in their greed for land, wealth, and power.

WIkipedia: A Century of Dishonor.

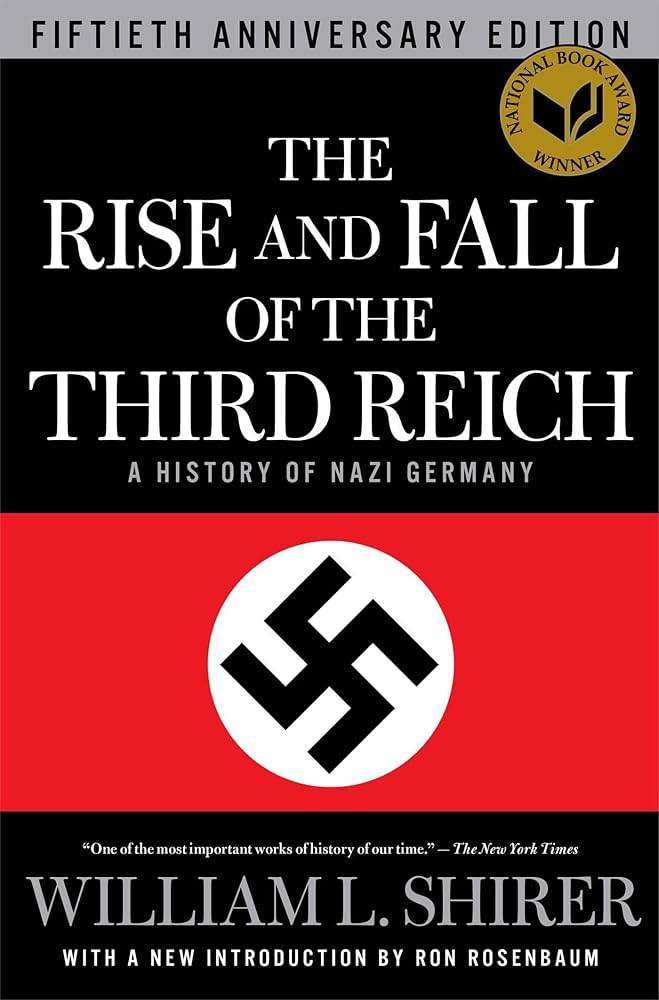

After that, it was no more tales of the brave pioneers for me. I read other books along the way, among them were:

- Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee

- Empire of the Summer Moon

- Killers of the Flower Moon

- In the Spirit of Crazy Horse

- Black Elk Speaks

When I had absorbed what had really happened in the settling of this country, I began to wonder how in the world these Native peoples could have survived what my ancestors had done? How had they hung on to their language and traditions, their religious beliefs? Why were they still here at all? I decided that from that point on I had more to learn from the survivors than I did from the so-called conquerors.

******

From the movie: Smoke Signals

******

From The New Yorker

******

******

There are a great many Native Americans whose stories I have heard, but none more impressive to me than that of Crazy Horse. A Lakota warrior and leader, he was one of those responsible for the victory at the Little Big Horn. Almost alone among famous Native men of his time, he refused to allow his image to be captured either by painting or camera, so we don’t know what he looked like. There are many photographs of Red Cloud and Sitting Bull, but none of Crazy Horse.

One of the last to come in for talks after numerous successful battles and skirmishes with the US Army, he was deceived and killed at Fort Robinson, in what is now western Nebraska.

The building where he was slain has been restored, and a plaque installed outside. His body was taken by tribesmen and buried in a location which remains unknown.

******