I realized recently that I hardly ever recount “doctor stories” in this blog. I have them, of course, after more than 35 years in those trenches. They tend to accumulate. Any line of work where you bump up against humanity in stressful situations will do that. Jobs like teacher, firefighter, law officer, soldier, etc. Each of them has their own set of stories, and mine are no more interesting or precious or enlightening than anybody else’s. Their only claim to fame is that they are mine, and meaningful to me in one way or another as a result. Here are a couple.

******

******

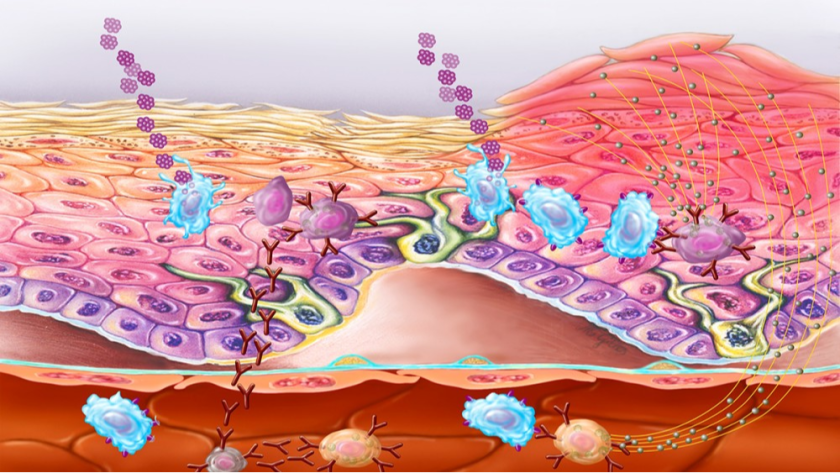

The small collection of patches and bumps and lumps on one’s skin that show up from time to time when one is young becomes a deluge of keratosis this and precancerous that as aging takes its toll on the dermis.

My dermatologist has even farmed out this tedious part of his business to a specialized PA so that he can devote himself to far more remunerative tasks, like fat freezing. Cosmetic procedures seem to be where it’s at if you want to buy a condominium of respectable size in a desirable location.

When a new patch shows up and looks benign to me, I use the OTC freezing kits you can buy almost anywhere. And for smaller lesions this works. But these rather wimpy tools are leagues away from what I had access to when I was a practicing physician. Back then I could call for a sturdy stainless steel thermos bottle containing liquid nitrogen, which was at a temperature of 320 degrees below zero. Now there’s a freezing agent with hair on its chest! (Note inexplicable use of archaic and sexist phrase).

There was a moment in my professional life when I had been on call too often and up at night too many times in a row and I said to my former wife (a registered nurse): “This is really too much. What would you think of my going back and taking a residency in dermatology?” Her answer took the wind out of that particular sail: “Why would you want to leave medicine?”

******

From The New Yorker

******

The New Yorker magazine of February 13 has in interesting article on space travel, including the fact that Musk and Cluck are excited about the prospect. I share their enthusiasm. In fact, I am so excited that I think this awesome pair should have the honor of being the first to make that voyage, and I suggest next Tuesday as a departure date.

******

******

An intern on pediatrics has been assigned the duty of being on call at the University of Minnesota Hospital on Christmas Eve of 1966. At sign-out rounds it looks to be a quiet evening. No known disasters are looming, and any patient who could be discharged is at home with their family. It is a cold night in Minneapolis, with temperatures already below zero by supper time.

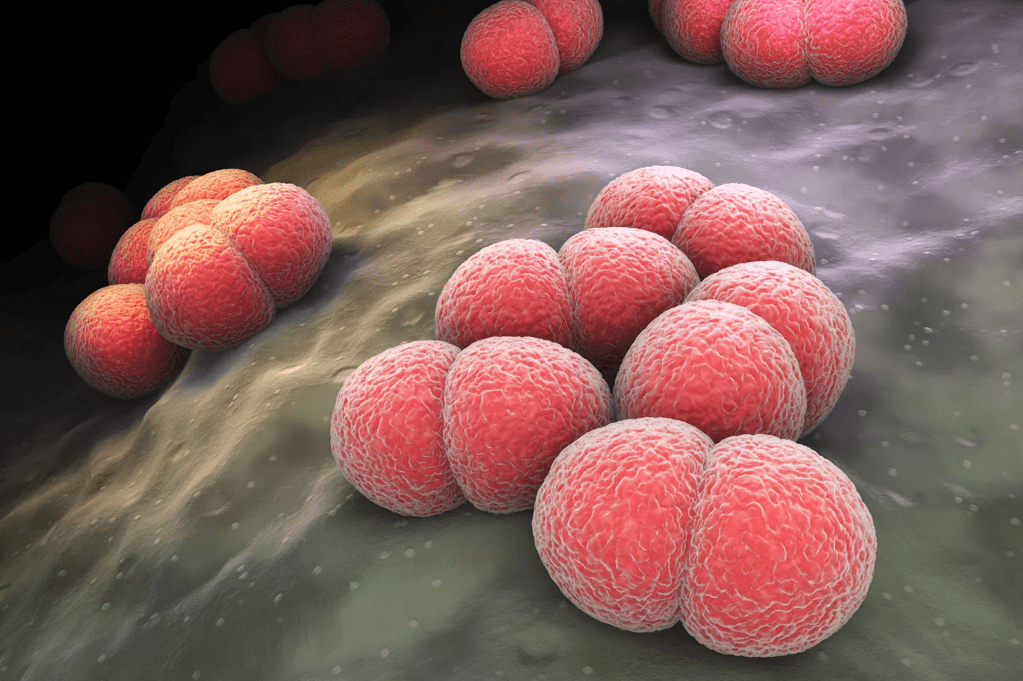

At 1900 hours there is a message from the emergency room. A sick infant, daughter of two graduate students, is waiting to be examined.The history is a brief one. The child has been ill for less than 24 hours, with symptoms of fever, poor appetite, and increasing listlessness. The examination reveals a generalized light pink rash, a neck that resists flexion, and the “soft spot” on the baby’s head bulges slightly.

The frightened parents are informed of the likely diagnosis and what must now be done quickly. A spinal tap reveals pus cells but does not give further clues as to the organism responsible. A sample is sent for culture. The working diagnosis is meningitis, etiology as yet unknown.

Treatment is immediately begun with what is called triple therapy – penicillin, a sulfa drug, and chloramphenicol. (This was at a time when the number of antibiotics available to a physician was very limited.)

The baby is moved to the infant ward at 2100 hours and at 2130 suffers her first cardiorespiratory arrest. The intern is able to resuscitate her using chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing. But there is to follow a second and then a third arrest. To the last one there is no response. Shortly after midnight resuscitative efforts are abandoned. The intern drops into a chair, exhausted, beaten.

In the morning the laboratory reports that they are growing the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis from the baby’s spinal fluid. Common name = meningococcus.

All personnel who came in contact with the child during its brief admission are advised to take antibiotics to try to protect themselves against developing the disease.This is implemented by placing a large jar of sulfa pills in the center of the infant ward, with dosage instructions taped to the side of the jar. Everyone was to help themselves to what they needed.

The intern reflected on his part in the resuscitations, grabbed a handful of the tablets and stuffed them into the pocket of his uniform. He turned and left the area. There were rounds to be made.

*

Such was the state of the art in 1966. So primitive by standards of only a few years later. There were no pediatríc ICUs, few antibiotics, and little existed of equipment that had been downsized to where it was suitable for use in the care of very sick babies. For example, intravenous infusions were gravity-fed, with infusion pumps not yet on the horizon, so maintenance of a working IV was an art form.

And that big jar of sulfa tablets … the self-prescription … looking back that seems more like practicing medicine in a war zone. Perhaps that was what it was.

******

******