What was the most intense year of my seven years of medical school and residency? No contest! It was my junior year in medical school. This was where we were turned out of the laboratories and libraries and shoved with little grace into the middle of a hundred patients’ stories at once. Stories that had predeeded our arrival and that would go on after we’d moved on to another clerkship.

[Definition: a clerkship was a portion of the junior year devoted to a specialty in medicine. A taste of everything, at least nominally to help the student pick out the discipline he or she would specialize in as a resident. The traditional clerkships were surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. ]

My first clerkship was on surgery, at the ancient Minneapolis General Hospital, a structure left over from the 19th century, with soaring ceilings, twenty-bed wards, inadequate wiring, no air-conditioning to speak of, and a patient population consisting of some of the nicest, some of the hardest-working, and some of the most dangerous people in town.

I loved it.

If you were being cared for on one of those ward there was only a curtain drawn to separate you from the other nineteen patients. There were few secrets to be kept, not when one loud-voiced medical attendant after another came to move or massage or feed you.

For the bookish student that I was it was almost unbearably exciting and completely exhausting at the same time. I would be on call every third night, and be up continuously that night. Next morning I would go to the outpatient clinics to act as if I weren’t half asleep, stumbling from litter to table to bed and seeing what kind of composure I could maintain in this new and desperate life.

The house staff, consisting of the interns and residents, and who were being abused in the same way, often regarded a medical student as yet another problem to be solved. Someone too earnest to ignore but too dumb to trust.

Perhaps one personal example will be enlightening.

I was spending the afternoon in orthopedic clinic, and had been assigned to change a cast on a twenty-two year old woman who had fractured her tibia weeks before. All I had to do was cut off the old cast and put on a new one, since by that time the bones had gone a long way toward knitting. The resident had informed me that the woman in question was a “working girl.” I was actually unfamiliar with that term but a couple of questions brought me right up to speed.

I thought to myself, well, then it’s nothing more than the meeting of two professionals and things ought to go well. I introduced myself, got out the cast saw and within no time at all removed the old and unsightly plaster.

Next I applied wrap after wrap of plaster cast material up and down the lady’s leg from just north of her toes to her upper thigh. If there was a bulge or a dent in this masterpiece I was creating I smoothed it over with a bit more plaster.

And then it was done, a thing of absolutely glistening porcelain beauty on one of the shapelier legs in Hennepin Country, I thought. I stood up and stood back and asked her to walk. The patient got to her feet, tried to take a step, and suddenly burst into tears. I had made a cast so heavy that she could not move it. It might have functioned as a construction pillar for a large department store.

I scurried to get the resident, who quickly diagnosed the problem. He consoled the sobbing lady and then, before he applied himself to taking off this monstrosity and replacing it with a workable version, sent me away for the afternoon. The look on his face was so clearly “Lord, what have I done to deserve this?,” that I did not quibble.

******

******

That same year, that same clerkship … a boundary was set for me. Remember I said that I was on call and up all night every three days? Well, on the days I wasn’t on call I would hang around the hospital, looking and listening to what was going on in that great beast. I loved every minute, even those where I screwed up or ran myself into walls. It was just such a vat of ferment.

But after two weeks of that very first adventure in the surgery rotation, I came home at eleven o’clock one night and the patient woman who was my wife was waiting up for me. I can’t quote her exactly but the sense of what she said went something like this:

“You have a wife and a baby daughter who need to see you. You can’t stay at the hospital when you aren’t required to be there and ignore us. If you keep doing that, one day we won’t be here when you do decide to come home.”

At that moment a boundary was set that I knew that I would violate at my own risk. I can’t say that there weren’t a few slips here and there, but there were significant periods of time between them. The problem was that those nights in the old barn that was General Hospital were among the most memorable … ever. So seductive. Such an attraction. Such a world had opened up there.

Aaaahhhhhhh … to be 24 years old again, wearing an ill-fitting scrub suit and eating free but tasteless cafeteria food and drinking free but thin coffee at three a.m. in the company of a cadre involved in fighting some of the best fights ever. Talk about your foxhole mentality … we had it.

******

******

This Christmas Eve Robin and I were by ourselves. We did leave the house to drive to the village of Ridgway (population 1200) at suppertime, where our favorite Thai restaurant was keeping its doors open. There are several Thai restaurants on the Western Slope where we live, but the very small one in Ridgway has an artist in the kitchen.

They are not afraid to charge what they think their food is worth, and the Mango Curry was $19.95, which is high for such a dish in this part of the world. But what a curry!

.

As I left the restaurant, I grieved that I hadn’t been able to completely empty my bowl, and had left an ounce or two of broth behind. But my lips had already passed from intense capsaicin-induced pain to complete swollen anesthesia and I feared that the rest of my face would follow suit.

******

******

We had one of the best Christmas Days this year, compliments of three good friends. All of the food dishes that Robin and I had prepared turned out well, the weather was impossibly beautiful, and the conversations ranged from the historically interesting to the nitty gritty of today’s politics.

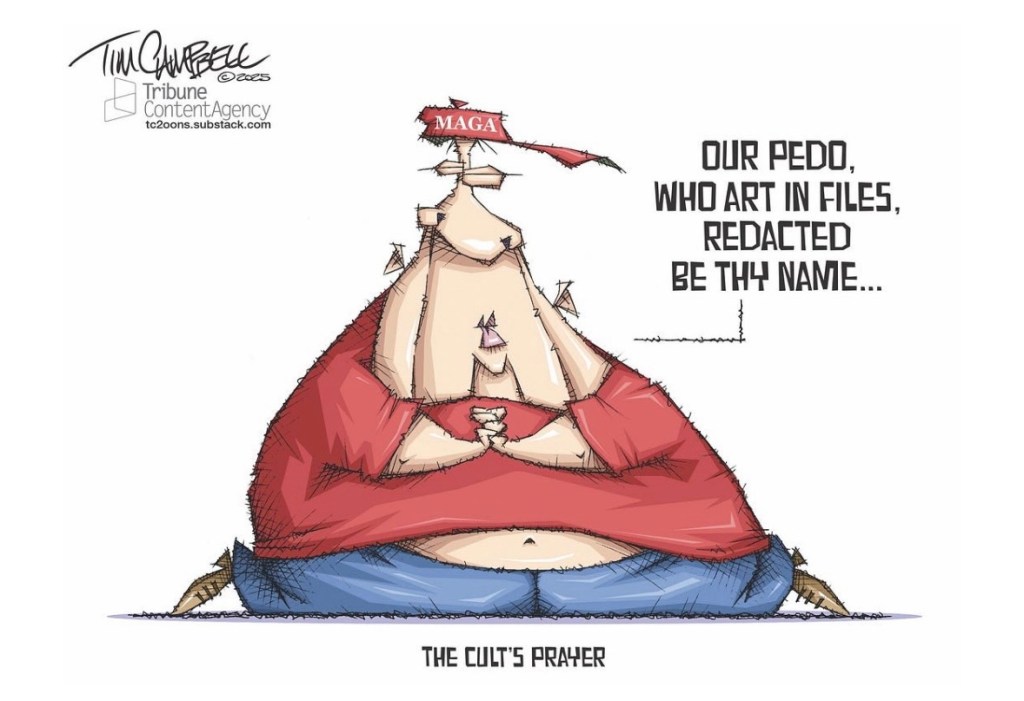

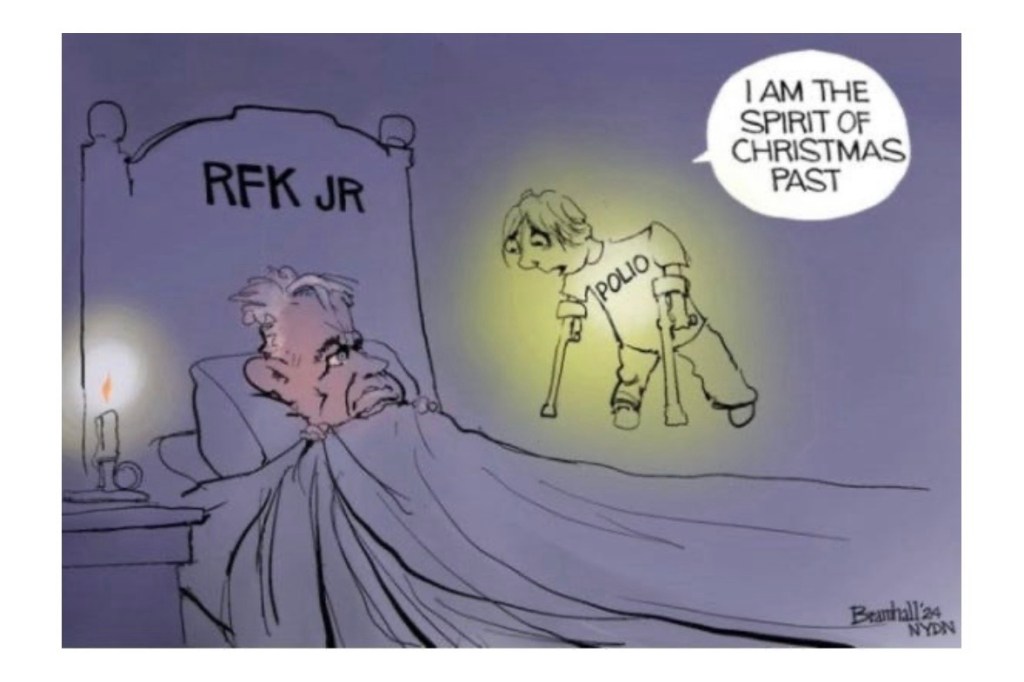

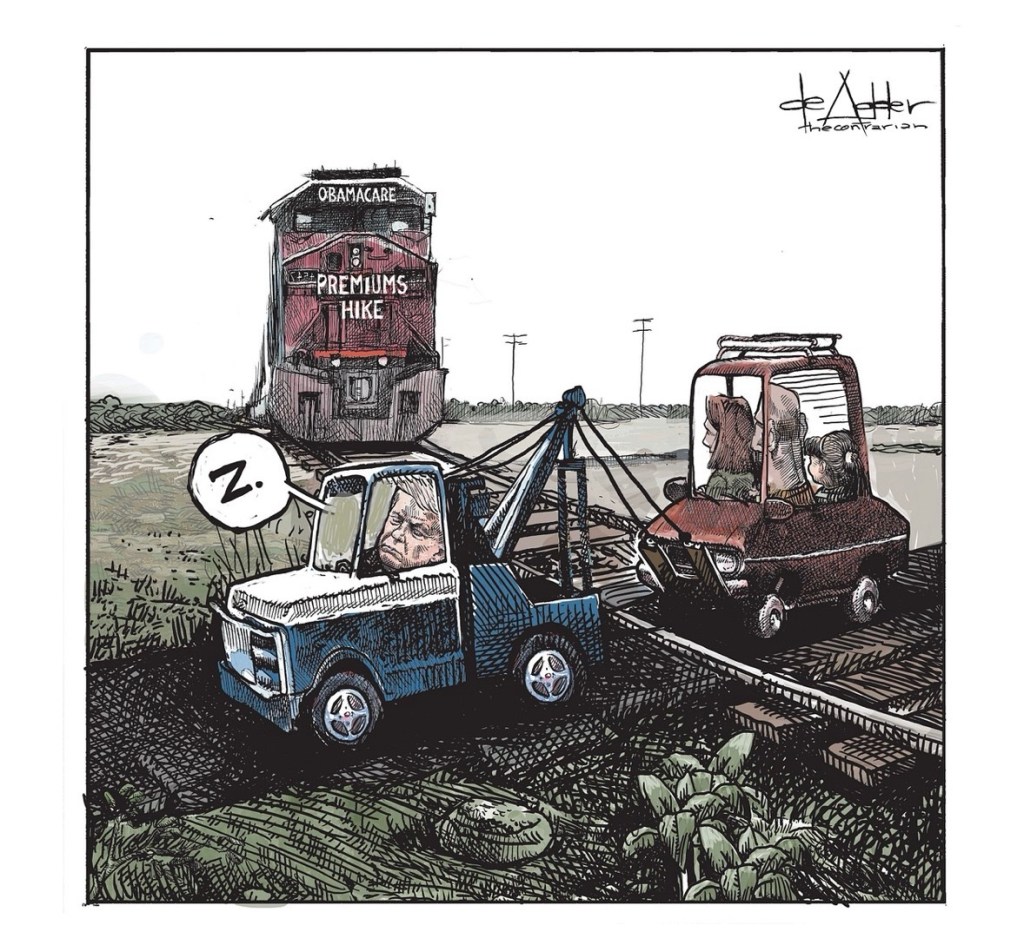

All five of us were liberals, two being Independents and three Democrats. At some point one of the our guests said something to the effect that when things are this bad there is nothing to do but hunker down until the bad guys go away. Give them enough time and they will implode, they said.

It was at exactly that point when the patriot Patrick Henry, whose words American schoolboys have had to learn for centuries, took over my body and began to speak. I began to make statements, outline resistance strategies, and make impassioned pronouncements as to the need for and the what of such resistance using words I only dimly understood and information to which I had little claim.

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Patrick Henry, March 23, 1775

When my mouth finally shut for a moment, there was no one more startled than I. I began to back off from what I’d said, and admit that there was no reason at all to listen to any of it because I was a known widely as a repeatedly convicted peddler of rampant nonsense. The rest of the group then settled down and lips that had tightened relaxed. When we parted amicably at the end of the evening and were still friends I silently thanked the gods for stopping me before I ruined what shreds of a reputation for probity that I still had.

But then Mr. Henry returned to say one more thing: “Well, Jon my boy, you’re a fainthearted patriot and that’s for certain. But give me a bit more time … I’ll make a bloody rebel of you yet.”

******

******